Ratna and Nadim Siraj

EmpireDiaries.com

(Originally published on May 16, 2023)

May 17, 2024: How many people in India know that there’s something called Mount Everest? Almost everybody. And how many Indians know about a mathematician called Radhanath Sikdar? Almost nobody.

From schools to literature, from history books to pop culture, from news debates to research centres, from think tanks to political circles – Radhanath Sikdar’s name appears only as a footnote.

Among those who have just about heard of him will tell you he was a Bengali man who calculated that the so-called Mount Everest is the world’s highest peak. Strangely, nothing more is known about his life – as well as his mysterious death.

For a tiny bunch of historians and writers who dedicated their lifetime studying him, the story of Radhanath Sikdar is much more than just about calculating the height of the world’s tallest peak. His story is an enormous, Himalayan mystery – unexplored, unsolved, and uncanny. A mystery that involves his unclear death, an unclaimed grave, an elusive letter, and a missing diary.

The story of Sikdar is an important chapter in India’s colonial history that has never been pieced together properly for reasons we don’t know.

Sikdar, who lived from 1813 to 1870 when the Indian subcontinent was illegally occupied by uncivil and predatory British invaders, wasn’t a mere survey department officer who calculated the so-called Mount Everest to be the tallest peak in April 1852.

He was the British colonisers’ most desired mathematician at that time, the first documented Indian freedom fighter, a labour rights campaigner, a pioneer of the first Bangla magazine on women’s rights called Mashik Potrika, and a scientist who rewrote geodesy, trigonometry, and meteorology.

Radhanath Sikdar: Britain’s Man Friday

It is baffling how little we know about this man, who was born in Calcutta (a British distortion of the current name, Kolkata). Sikdar was the British East India Company’s top-most survey officer for the corporate empire’s intelligence project to map the Himalayan range. The team-leading position he held was called ‘Chief Computor’ at that time.

During those days, scientists, mathematicians, and experts who could solve complex mathematical problems were called ‘professional computors’ (much later, with the advent of computerised technology, the word ‘computor’ began to be spelt as ‘computer’).

Sikdar used his mastery in geodesy, maths, and science to help turn a nondescript ‘Peak XV’ in the Himalayas into what became the world-famous ‘Mount Everest’. Unfortunately, the credit for it is wrongly given to George Everest (pronounced ‘eev-rest’ not ‘ever-est’), a former Surveyor-General of India who was not at all associated with the calculation of the world’s tallest peak’s height or its identification.

NOTE: Further into this article, we have referred to the world’s tallest peak by its last-known technical name of ‘Peak XV‘ and not as ‘Mount Everest‘. It was arbitrarily named Mount Everest by the British invaders. By doing so, they violated the convention of assigning local names to newly discovered Himalayan peaks. Therefore, we have avoided using the British name wherever we could.

Five Puzzling Questions

At EmpireDiaries.com, we tried to dig deep into the life and times of Sikdar. The deeper we dug, the more intriguing his life story turned out to be. As we began to follow the leads, we bumped into several unanswered questions. There are too many of them, and they are too disturbing to ignore, as also acknowledged by researchers who have written revealing books on him.

Here is a round-up of the missing pieces of the puzzle surrounding Sikdar’s life story.

1. Where Is His Letter?

As the British East India Company’s Chief Computor and the point-man in Calcutta for the Great Trigonometric Survey of India (GTS) project, Sikdar calculated in April 1852 that Peak XV in the Himalayas – and not Mount Kanchenjungha as previously assumed – is the world’s highest mountain, measuring 29,000 feet.

But strangely, Sikdar’s official communication to Andrew Scott Waugh, his boss at the GTS in Dehradun (now the winter capital of Uttarakhand), about this enormous discovery cannot be traced. It is missing.

Sikdar’s letters to Waugh right before the discovery and right after it have all been located at the National Archives of India in Dilli. They confirm that Sikdar and Waugh were constantly exchanging minute details about the Himalayan mapping project via official correspondence. Yet, the most vital piece of communication can’t be found. Where is it?

2. Died Or Disappeared?

On May 17, 1870, 18 years after Sikdar’s discovery about Peak XV’s height, the Bangla and English press in Calcutta reported that he died at the age of 56 in the riverside town of Chandannagar (originally called ‘Chaander Nogor’) in Bengal’s Hooghly district, where he resided during his last few years. But there was no mention in any of the news reports and obituaries of exactly how he died. There simply are no details.

Mysteriously, no one reported or seemed to know about precisely what happened to Sikdar’s body upon his presumed death. Fast forward to 2023 – we still don’t know anything.

So, did Sikdar at all die on that day? Did he disappear on that day? Why is so little known about his whereabouts, if he died a natural death? It is an inexplicable mystery, considering he wasn’t an ordinary person – he was someone who captained the high-profile British quest for mapping the Himalayas and measuring its highest peaks.

Also, who informed the news publications of his presumed death, which they reported without citing any details? We don’t know that yet.

3. Why Chandannagar?

In 1849, as the GTS Chief Computor, Sikdar was transferred from the Survey of India’s Dehradun HQ to its Calcutta office. However, despite getting moved to his hometown Calcutta, he took up residence 50km away from the city – settling down in the town of Chandannagar in Bengal’s Hooghly district.

It is not known whether he first shifted to Calcutta and later relocated to the riverside town, or whether he directly moved to Chandannagar from Dehradun. What is known is that he used to commute daily from his Chandannagar residence to his office in Calcutta’s Park Street – presumably taking the ferry across Hooghly River.

The big mystery is – why was such a high-profile official of the Survey of India, who was heading the top-secret Himalayan mapping project, residing far away from his work station in Calcutta, which was also his hometown? Was he forced to do so? Or did he do it deliberately? If so, why would he do that?

Also, why Chandannagar, of all places, if he really wanted to avoid residing in Calcutta for some reason? Calcutta was a major base of the British East India Company, but Chandannagar was the base of a rival of the British at that time – the French colonisers.

Coming back to the puzzling question – why would a British-appointed high-profile official reside in a town controlled by the rival, French crown? It made no sense.

4. Real Or Fake Grave?

About 140 years after Sikdar’s death (read: disappearance) in Chandannagar, an unmarked grave at a Christian cemetery in the heart of that riverside town suddenly sparked curiosity.

Some people in Chandannagar kicked up a storm, claiming to have found Sikdar’s grave. Citing circumstantial evidence, they insisted that he had converted to Christianity during the closing decades of his life, and so, upon his death in French-occupied Chandannagar, was buried at the Sacred Heart Church’s cemetery.

Yet, the church’s burial records don’t confirm the claim about the grave. According to the church’s official record books, no one by the name of ‘Radhanath Sikdar’ is buried at the cemetery. So, why was there a buzz surrounding the mysterious grave? Whose grave is it?

5. Where Is His Diary?

In the decades following Sikdar’s reported death in Chandannagar, his personal diary somehow went missing. It was last known to have been in possession with a descendent of a Bengal-based Derozian, Ramgopal Ghosh. But he had reportedly refused to share the precious diary or its contents publicly despite requests from various people.

Sikdar enthusiasts and historians are today looking for that missing diary, which could hold the answers to some of these questions.

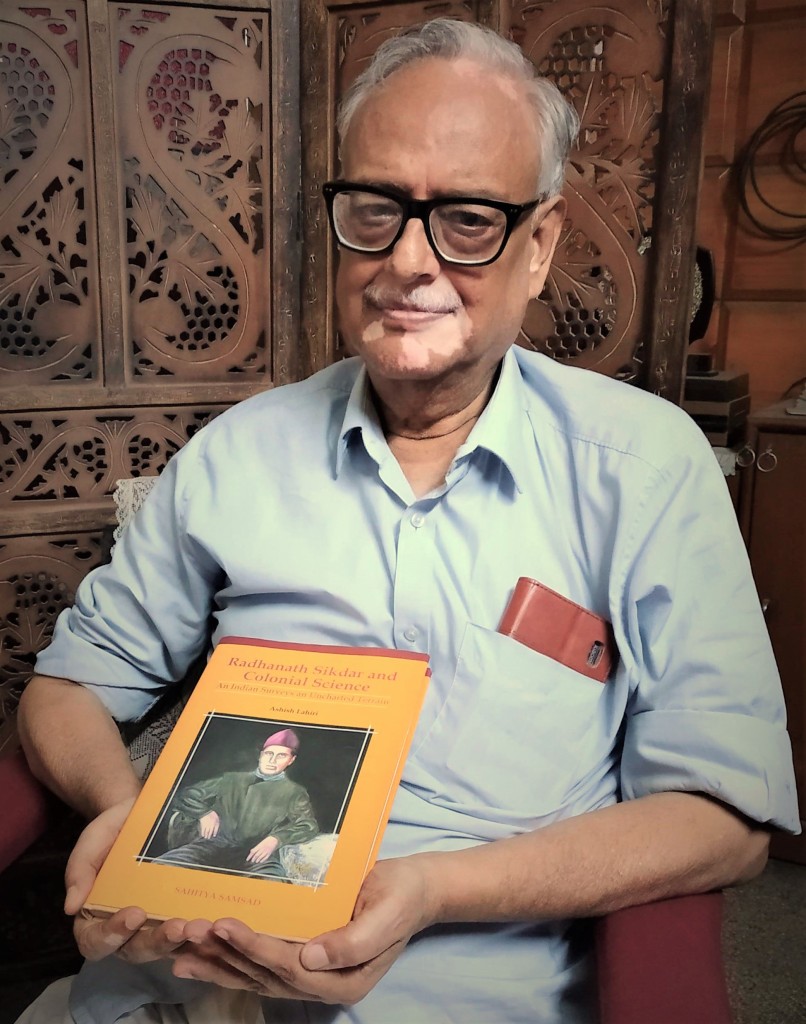

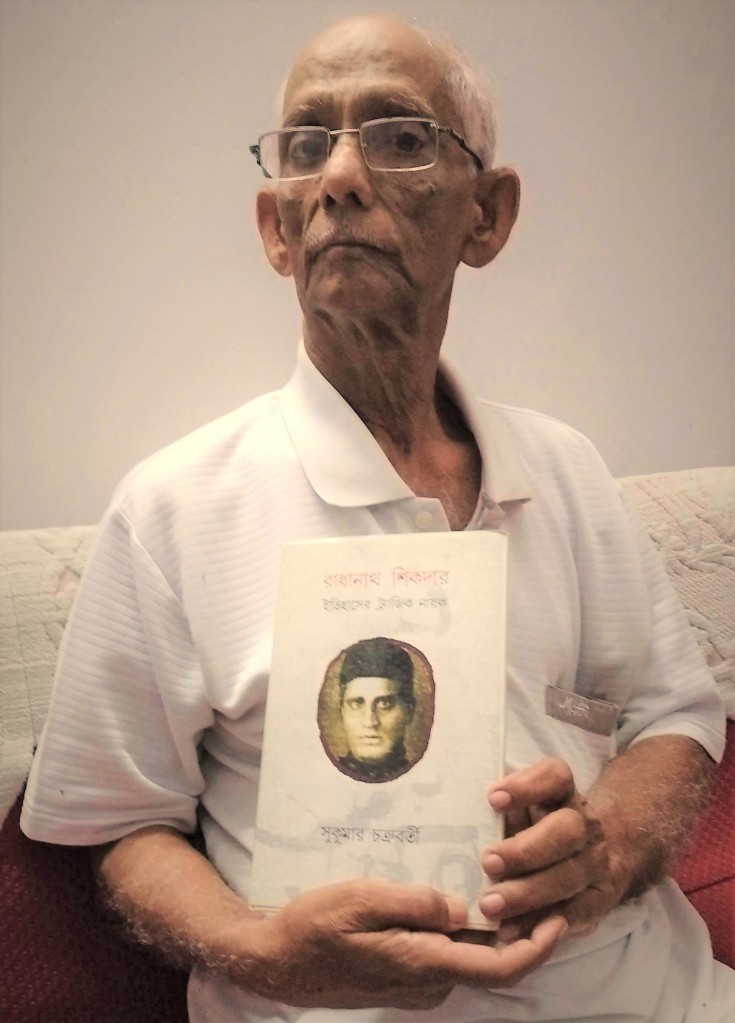

In light of these unanswered questions, we tried to put together his life story based on priceless insights shared by Ashish Lahiri, Sukumar Chakraborty, Dr. Sankar Kumar Nath, Kalyan Chakraborty, and Tushar Bhattacharya.

Lahiri is a Kolkata-based author who has written multiple books on Sikdar. He is also a campaigner for rationalism and atheism, having written firebrand books on these subjects. Sukumar Chakraborty is a Chandannagar-based mountaineer and author who has written a book on Sikdar.

Dr. Nath is a Kolkata-based surgeon who has written a book on Sikdar and is busy investigating further into his life story. Kalyan Chakraborty is a Chandannagar-based mountaineer and globetrotter who runs a knowledge centre dedicated to Sikdar. And Tushar Bhattacharya is a former surveyor, a lifetime Sikdar researcher, and a theatre personality in Chandannagar.

His Jorasanko Roots

For most people, the neighbourhood of Jorasanko in north-central Kolkata is like a pilgrimage site – it is the ancestral home of Rabindranath Thakur, the most celebrated Bengali poet, composer, and playwright of all time. Yet, very few people know that the man who calculated the height of the world’s tallest mountain was also born in the same locality.

Sometime in October 1813, Tituram Sikdar, a man of modest earnings and residing in his ancestral house in Jorasanko, was blessed with a son whom he named Radhanath. There is no evidence yet of the birthdate. Historians say Wikipedia misleadingly claims that he was born on October 5. The American information website doesn’t cite any sources.

Sketchy details are known about Radhanath’s humble beginnings. His mother’s name is not yet known. All that is known of his childhood days is that he was precocious, had a brother named Srinath Sikdar, a sister, and possibly another sibling – whose names are not yet known.

A conflicting and unverified account says Radhanath may have been born in his maternal uncle’s house in Calcutta’s Ahiritola area.

Some historians say that during the time of the Nawabs of Bengal, Radhanath’s ancestors were a well-known family of robust people, serving as police personnel.

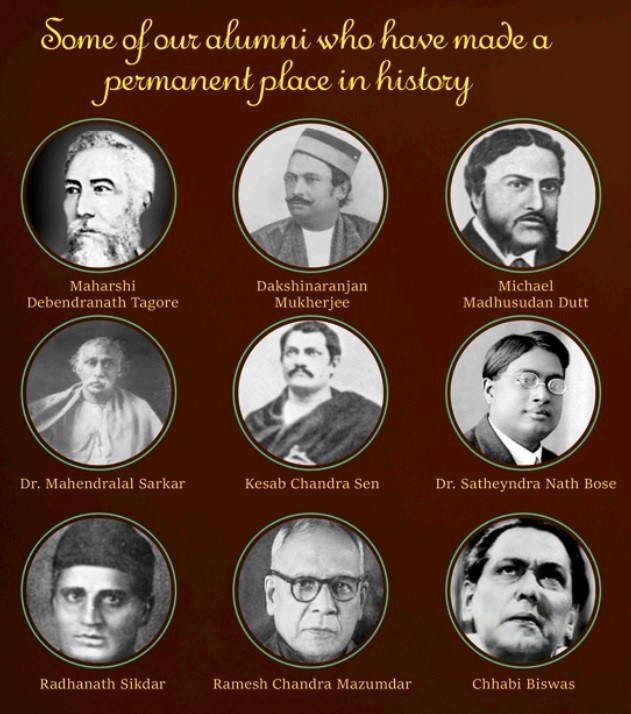

Young Radhanath and his brother Srinath began their studies at Kamal Bose’s school in Jorasanko. In 1824, when Radhanath was 11 years old, he was sent to Hindoo College in Calcutta (now called Presidency University) along with his brother Srinath. Hindoo College was a secondary school at that time.

A Brilliant Student

In school, Radhanath emerged as a brilliant student, bagging a scholarship of Rs 16 in ‘First Class’, which is today’s equivalent of Standard X for the age group of 15-16 years.

The quick-thinking, Bangla-speaking Radhanath quickly went about mastering multiple languages – English, Sanskrit, French, Greek, and Latin – while he immersed himself in mathematics and philosophy.

During his seven-year spell at Hindoo College, he was deeply influenced by Indian poet and maverick thinker Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, who taught at the school at that time.

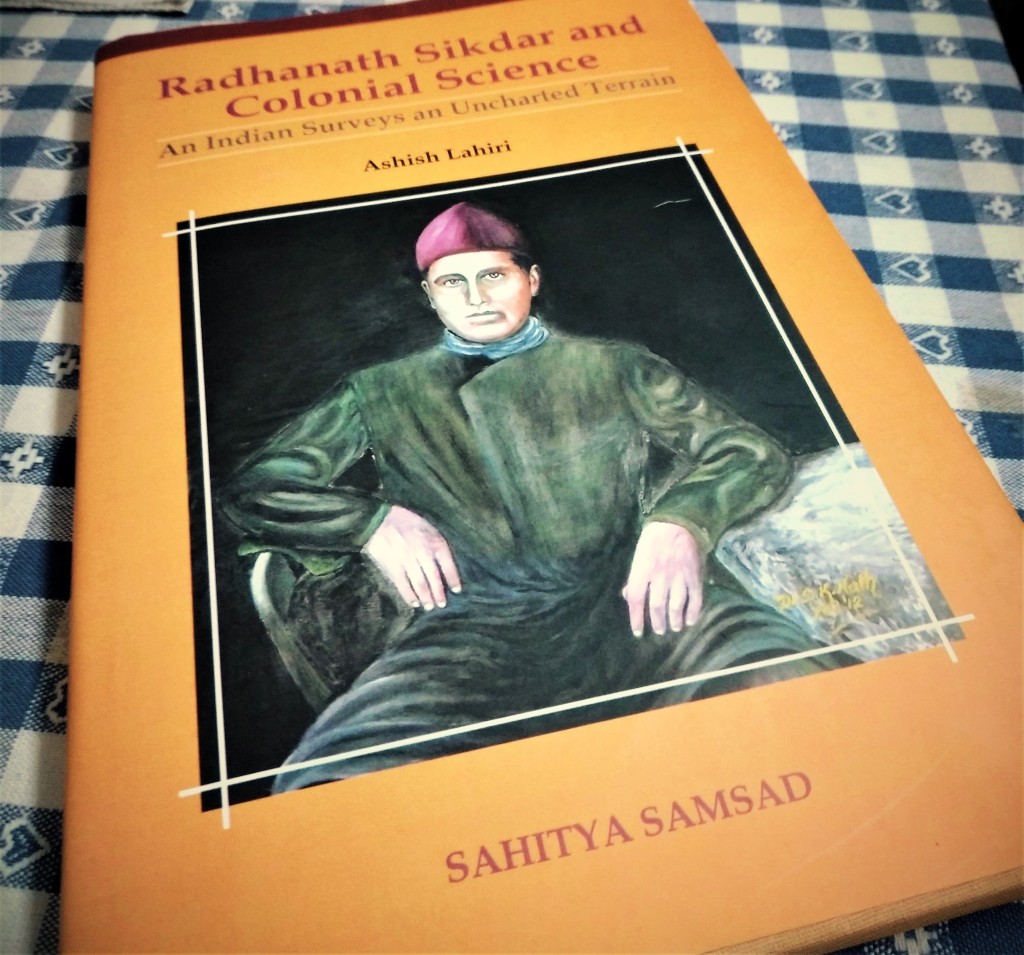

Historian and writer Ashish Lahiri writes in his book, Radhanath Sikdar and Colonial Science: An Indian Surveys an Uncharted Terrain, that a progressive-minded Sikdar at that time turned down his mother’s proposition that he should marry an eight-year-old girl. Sikdar eventually went on to spend the rest of his life as a bachelor.

In school, Sikdar was particularly close to one of his teachers, John Tytler, who encouraged him to take lessons in western science, and study Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica.

Newtonian Maths

Many years later, in the obituary of Sikdar in 1870, the Indian publication Hindoo Patriot noted that he was the first Bengali youngster to receive lessons in the maths invented by English mathematician Newton and French polymath Pierre-Simon Laplace.

A major turning point in the young student’s life came in December 1831, when his teacher Tytler – charmed by his mathematical capabilities – recommended him for a full-time job at the British East India Company’s Survey of India, headed by George Everest.

On December 19, 1831, at the age of 18 and with his studies still incomplete, Sikdar took up the offer to work as a ‘Computor’ for the Survey of India’s special project, the GTS – Great Trigonometrical Survey of India. He joined for a salary of Rs 40 per month.

He entered the world of geodesy and surveying just like a duck taking to water. In the years that followed, he became a key member of Everest’s team, eventually getting entrusted with the secretive mission to figure out the highest peak in the Himalayas.

Meanwhile, nothing significant is so far known about his immediate family members.

GTS, Great Arc, And British Intelligence

The story of Sikdar sends us back to the time when British colonialists carried out the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India – or the GTS. After the British invaders defeated Tipu Sultan of Mysore (now Mysuru) in the summer of 1799, they realised that the coast was clear to launch a full-spectrum capture of the Indian subcontinent.

To be able to do that, the British East India Company needed a clear idea of the shape, size, and contours of the landmass they were targeting to colonise and plunder. They needed precise maps and a detailed geographical layout of the subcontinent to launch their imperialist project.

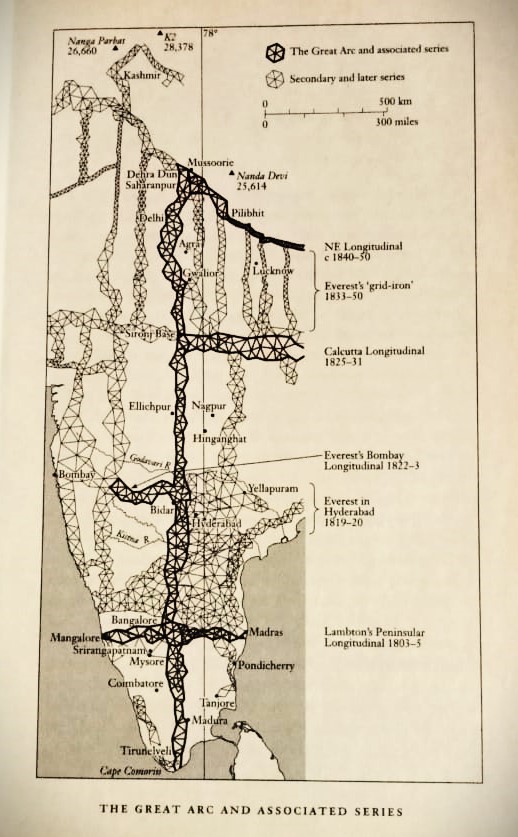

The GTS was born out of the desperate need of the British opportunists to map the Indian subcontinent from east to west, and north to south. It was a sophisticated intelligence operation commissioned by the British East India Company in 1802, and it was concluded by the corporation’s rival, the London-headquartered British monarchy, in 1871.

The Power Transfer

The illegal British control of the Indian subcontinent changed hands from the British East India Company to the British royal family right after the Rebellion of 1857, an inspiring chapter in India’s fight against Western colonisation.

The changeover is not written in schoolbooks and mainstream history as a power transfer between two competing Britain-based imperialist forces. Instead, it is portrayed as a seamless handover of the keys to the Indian subcontinent from the hands of the company to the monarchy.

The crowning glory for the GTS was to find the correct heights of a string of mountains in the Himalayas – home to some of the world’s highest snow peaks. Since Sikdar was a natural team leader and a mathematical wizard, he was handpicked by the crafty British to head the mission.

Human ‘Computor’

After joining the GTS as a computor, Sikdar operated from Sironj (Madhya Pradesh) and Dehradun (Uttarakhand). In the days that followed, he outshone his colleagues with his unmatched knowledge and innovative application of trigonometry, and therefore, quickly became ‘Sub-Assistant Computor’ in 1832, now drawing a monthly salary of Rs 107.

He quickly rose through the ranks to become the ‘Chief Computor’ of the GTS in 1845. He stood out from the rest of the computors because he gave the field of geodesic survey a new meaning with his inventive style of work.

As the team leader, he studied the top-secret readings dispatched to him in his Calcutta office from seven locations around the Himalayan peaks. It is well documented that he used his expertise in maths, trigonometry, and geodesy to calculate and conclude that Peak XV was the world’s highest peak.

Top-Secret Mission

Andrew Scott Waugh was the Surveyor-General of India at that time, having succeeded George Everest. He was Sikdar’s immediate boss during those few years of intense drama and dark politics at the GTS.

The GTS’s Himalayan mapping mission was a smaller part of a much larger intelligence project of the British East India Company – called the ‘Great Arc’.

The Great Arc was a massive British intelligence programme aimed at surveying the meridian arc or the longitudinal arc from the southernmost point of the Indian peninsula all the way up to the region spanning Nepal.

The Great Arc project ran from 1806 to 1841, covering around 2,400km. The credit for the project is given to George Everest, who was Surveyor-General of India from 1830 to 1843, and after whom Peak XV was named in 1865.

Expectedly, the Royal Geographical Society in London doesn’t acknowledge that the Great Arc was an intelligence project, instead, claiming that it only “aimed to measure the curvature of the Earth”.

No Link Between Peak XV, George Everest

While people around the world are misled into believing that George Everest was involved with the discovery of Peak XV’s height, historians unearthed something quite the opposite.

One of them is Ashish Lahiri, the Kolkata-based rationalist who has written three books on Sikdar, one of them being the first ever book on the mathematician in English.

Lahiri’s first book on Sikdar is called Radhanath Sikdar: Beyond the Peak. Later, he wrote two more books – Dwi Shotoborshe Radhanath Sikdar (Radhanath Sikdar on his 200th birth anniversary) in Bangla, and Radhanath Sikdar and Colonial Science: An Indian Surveys an Uncharted Terrain in English.

“Many people don’t know that George Everest wasn’t interested at all in the project to map the Himalayas. He simply wasn’t interested in the mountains. It is something that we now know for sure. In fact, his biography says so. Rather, Everest was engrossed with the Great Arc project.

“The Great Arc was a stupendous mission. It was one of the greatest jobs in the history of surveying. But when it came to the Himalayas, Everest was least interested,” said Lahiri, who is also a lexicographer.

“It was a big joke,” said Lahiri about the move to rename Peak XV as Mount Everest. “Everest had nothing to do with that peak. He had retired in 1943 – long before Radhanath calculated the peak’s height [in 1852].”

Lahiri also pointed out that Everest wasn’t an easy person to work. “It is documented that he was extremely bad as a human being,” he said. Everest was indeed never known to have said anything good about the people he worked with in the Survey of India – except for Sikdar, whom he liked perhaps for strategic reasons. Having said that, Everest never jumped to Sikdar’s rescue whenever the latter had run-ins with British officers.

Big Cats, Wild Bears

The Great Arc as well as the Himalayan mapping project were no easy tasks, as evident from historical reports of the deaths of Indian and British officers and workers who couldn’t survive the unforgiving jungles. For all its spectacular beauty, the Himalayan terrain was hostile towards them. There were infectious outbreaks, and a perpetual threat from predators in the forests of the high slopes.

“I was a mountaineer for many years. Take it from me, survey work was very difficult in the Himalayas during those days,” asserted Sukumar Chakraborty, a former mountaineer who researched Sikdar’s life and wrote a book on him in Bangla, Itihaash-er Tragic Nayok (History’s Tragic Hero).

“Mapping the Himalayas was the most difficult job. The project’s base itself was at 16,000 feet. So, you can imagine the difficulty level. The surveyors and their teammates had to negotiate big cats and wild bears, who often took away the [Indian] coolies,” he said.

Role Of Theodolites

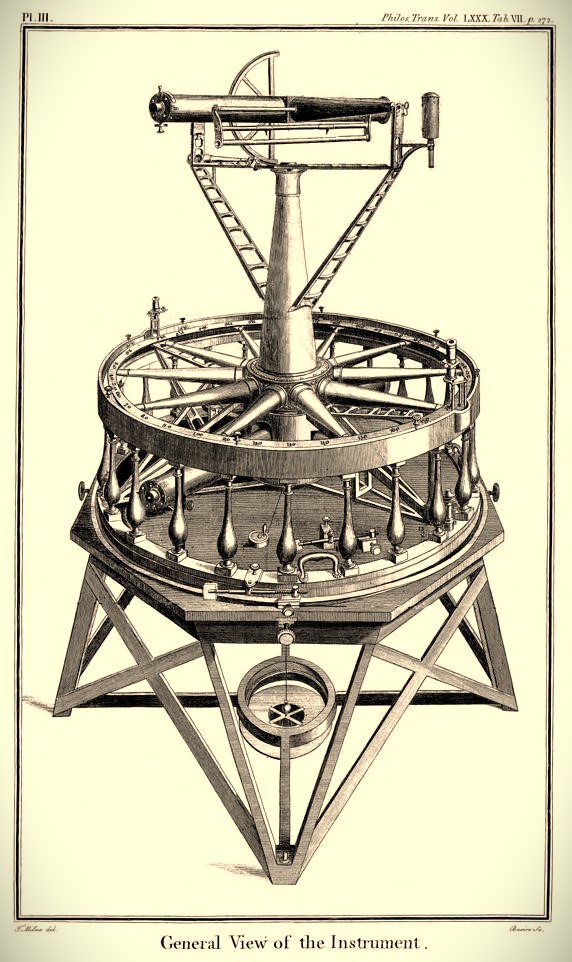

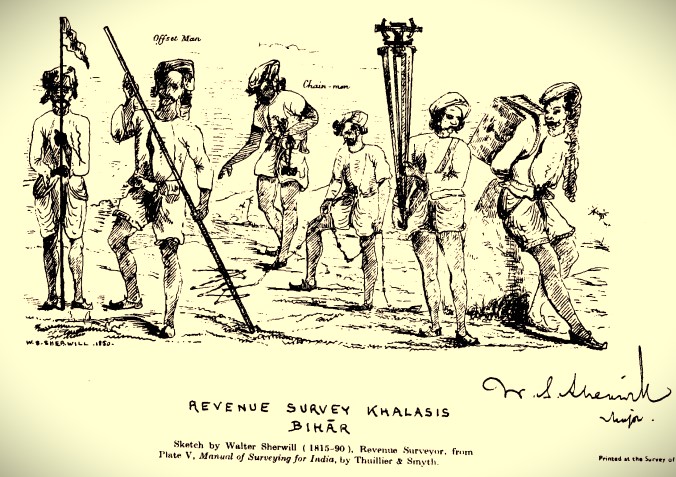

“Many people don’t realise today that the theodolite was a very primitive equipment back in the 19th century. It was hefty, difficult to carry around, and weighed tons,” said Sukumar Chakraborty.

Theodolites are surveying instruments whose origins go back to 16th-century Britain. English mathematician Leonard Digges is known to have made its use popular among surveyors. It is an instrument used to measure horizontal and vertical angles on terrains.

Theodolites as well as strategically placed survey towers were part of the GTS’s set-up as its officers went about mapping the subcontinent during the 19th century.

Surveying: Then And Now

Tushar Bhattacharya is a Chandannagar-based former government surveyor who holds Sikdar in high esteem. Now a theatre artist, Bhattacharya says the art and craft of surveying has seen a huge transformation from the time of the GTS.

“The two eras cannot be compared. During the 19th century, surveyors used to manually take geodesic readings using ‘Vernier theodolites’. They were extremely heavy and clunky, and required well-trained and experienced people to operate them. It was also extremely time-consuming,” said Bhattacharya. “Today’s theodolites are so scientifically advanced that surveyors practically don’t need to do anything. The theodolites have automatic features. They do everything on their own. And they are quick.”

The surveyors who took the readings of Peak XV during the 1850s mission used Vernier theodolites, which were also used in building the iconic Howrah Bridge on Hooghly River in Kolkata.

“Gone are the days when a survey department needed highly skilled surveyors to handle the Vernier theodolites. Today, we have high-tech instruments, such as Total Stations, DGPS, and Scanner,” said Bhattacharya. “They are light, they take readings on their own, and they are accurate. You just need entry-level people to handle them.”

So, does Sikdar’s job profile of Chief Computor exist today in these times of automation? “No way,” laughs Bhattacharya. “The jobs of human computors don’t exist anymore. Modern-day theodolites themselves take care of that. Gone are the days of manual calculations, and manual processes such as handling log tables, coordinates, angles, distances, and trigonometric formulas.”

Historical Names

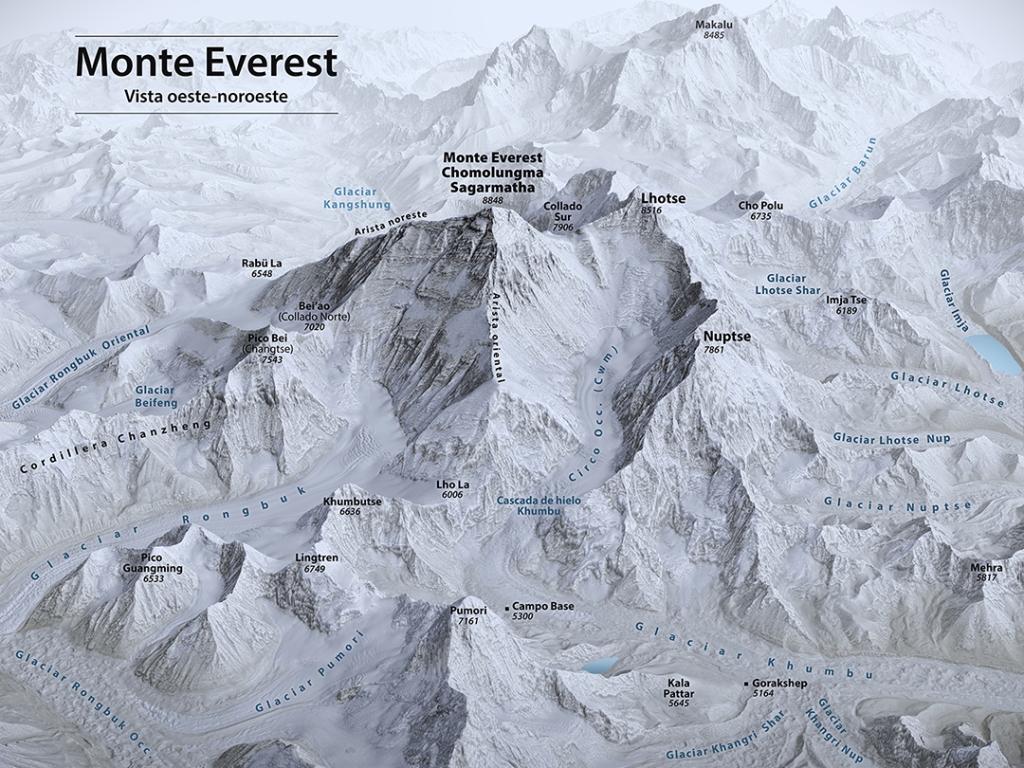

Peak XV, which lies on the Nepal-China border, has been a boiling pot of multiple names for centuries. Its official height has been changing for the past few decades, and the debate surrounding its name has been raging for much longer.

The Tibetan name of the peak – ‘Qomolangma (Holy mother)’ – was first recorded in 1721 in the ‘Kangxi Atlas’ maintained at that time by Emperor Kangxi of Qing China. The word Qomolangma is pronounced chomo langma.

Twelve years later, following explorations carried out by Jesuit missionaries from Beijing, the peak’s name was published as ‘Tchoumour Lancma’ – a French distortion of the Tibetan name – on a map published in 1733 in Paris by French cartographer JBB D’Anville in the ‘Carte Generale du Tibet ou Bout-tan’. This episode is documented in Craig Storti’s book, The Hunt for Mount Everest.

Earlier on, in mainland China, the peak used to be called ‘Zhumulangma Feng’, while it had another name as well – ‘Shengmu Feng (Holy mother peak)’. Much later, in 1952, the Chinese government phased out these names, and officially adopted the name ‘Qomolangma’.

Also, over the past, many locals in and around Darjeeling town called the highest peak ‘Deodungha (Holy mountain)’, while all across Nepal, it has consistently been called ‘Sagarmatha’.

After the British East India Company invaded the subcontinent, they spotted the highest peak as a “stupendous snowy mass,” before naming it ‘Gamma’ during the 19th century. A few years later, the Survey of India renamed it ‘Peak b’, then ‘Gamma/b/h’, before the GTS labelled it as ‘Peak XV’. It was assigned that name because it was the 15th of 79 Himalayan peaks that the GTS had targeted to map and measure.

Once the technical name of Peak XV was decided upon, the British mission to investigate whether it was the world’s highest mountain was underway in 1849 under Sikdar’s leadership.

Transfer To Calcutta

While Sikdar, the GTS Chief Computor, was tasked to lead the big mission, he was strangely transferred to Calcutta at that time, from where he would carry on piloting the top-secret project. He operated from his new office in Calcutta’s Park Street, and Dehradun remained the GTS’s headquarters, where his boss Andrew Waugh was based.

As pointed out earlier, it is baffling that when Sikdar was transferred to Calcutta, he decided to reside 50km away, in the riverside town of Chandannagar in Bengal’s Hooghly district, commuting daily to his Park Street office from there.

And Chandannagar was at that time the base and bastion of the French colonisers, who were bitter rivals of the British East India Company.

Historians are still perplexed why Sikdar decided to reside in the rival town of Chandannagar while serving as a top-level British-appointed officer.

Between 1849 and 1850, a team of GTS surveyors observed Peak XV using theodolites from six different observation locations, called stations. The survey team covered an arc around the Himalayan peak to study it, but they were forced to operate from a distance. They couldn’t get up close to the cluster of the highest peaks because of tensions between the British and the Chinese.

John Armstrong, John Peyton, John Hennessey, Charles Lane, and James Nicholson were some of the British and Anglo-Indian members of the team that reported to GTS chief Waugh in Dehradun and shared their readings with Sikdar in Calcutta.

They took the readings from various angles between November 27, 1849 and January 17, 1850, and then passed them on to Sikdar in his Park Street office. According to another researched account, raw data using theodolites was taken from seven observation stations, not six. Readings were taken at Jirol, Mirzapur, Janjpati, Ladiva, Haripur, Minai and Doom Dongi.

Armed with all the readings, Sikdar focused on scrutinising the readings in order to piece together how high Peak XV and its neighbouring peaks were.

British Parliament

It is around this time that Sikdar got a rare mention in the power corridors of London. According to a 2013 article written by Utpal Mukhopadhyay in the magazine Dream 2047 run by Vigyan Prasar, India’s science and technology department, an internal report presented to the British parliament on April 15, 1851 mentioned the Indian mathematician.

Regarding the work of the GTS, the report said, “A more loyal, zealous and energetic body of men than the sub-assistants forming the civil establishment of the survey department is nowhere to be found and their attainments are highly creditable to the state of education in India. Among them may be mentioned as most conspicuous for ability, Babu Radhanath Sikdar, a native of India of Brahminical extraction whose mathematical attainments are of the highest order.”

Meanwhile in Calcutta, after a couple of tense years and hot-headed correspondence exchanges with his boss Waugh in Dehradun, Sikdar made the discovery that changed the course of mountaineering history. The heated exchange of letters is best documented in an investigative book by historian Ashish Lahiri.

The Big Breakthrough

In April 1852, based on painstaking calculations and rigorous analyses of the survey data, and after factoring in deviations, errors, and atmospheric refraction, Sikdar concluded that Peak XV was the highest mountain on the Himalayan range. The precise date when he made the conclusion is not yet known.

In one swipe, Sikdar, 39 at that time, trashed the long-held belief that Kanchenjungha was the world’s highest peak. The Kanchenjungha peak, which lies 124km to the east of Peak XV, is 28,169 feet high.

It is worth noting that the year in which Sikdar was busy with the Himalaya mission, he was also appointed by the Survey of India to head Calcutta’s meteorological observatory, starting on September 30, 1852. Essentially, he was doing two full-time jobs at the same time, from the same office.

Going by the high frequency of correspondence exchange between Sikdar and Waugh, it can be assumed that the Calcutta-based Chief Computor would have communicated his groundbreaking discovery about Peak XV’s height to the GTS Superintendent in Dehradun without delay. However, that particular piece of communication from Sikdar to Waugh is untraceable.

Treasure Hunt

A few years ago, writer-researcher Ashish Lahiri visited the National Archives of India in New Delhi, hoping to trace that elusive letter. Although he located a treasure trove of correspondence exchanged between the two, he didn’t find the all-important letter.

Lahiri accessed the official letters ranging from January 7, 1851 to November 18, 1861 between Sikdar at his Calcutta office and various Survey of India officials, especially Waugh in Dehradun.

“Pursuing the matter all the way to Delhi was a thrilling experience,” recalled Lahiri. “It took me a while to find the records. They were preserved in large notebooks in the department of cartography at the National Archives. As I sifted through the letters exchanged between Radhanath and Andrew Waugh, I was inching towards the phase [in 1852] when that important communication would have happened. It was thrilling. I was so excited that I rang up a friend from there.”

However, Lahiri was perplexed that the document he was looking for was not there. He located the letters that were exchanged between Sikdar and Waugh leading up to the big discovery, and after that. But the letter about the final calculation? It was not there. He asked around at the archives office, but no one could help him.

“Something is possibly wrong. I don’t know exactly what it is, but it does strike me as odd,” Lahiri said. “I even found the document about the final calculation that Radhanath had done. But I just don’t know why this letter was missing. It’s a million-dollar question. Something is not right about it, I suspect.”

Was it a case of the British colonisers trying to sideline Sikdar because he was not a Britisher? “As I said, something wasn’t right. Possibly, racism could be the issue; skin colour could be a factor,” Lahiri contemplated.

In his findings about Peak XV, Sikdar concluded that its height was precisely 29,000 feet. But in the following weeks, Surveyor-General Waugh, having accepted Sikdar’s calculations as correct, decided to tweak the figure to 29,002 feet. Some researchers speculate that Waugh added two feet to the figure for good measure – to ensure that it doesn’t appear like a rounded-off estimate.

Uneasy Silence

One would imagine that Sikdar’s stature in the Survey of India circles would have grown enormously after his big discovery. But that was not to be. Despite the achievement, the GTS kept him posted away from the Dehradun headquarters, at the same Calcutta office.

In fact, the Survey of India went radio-silent after the discovery for four long years, from 1852 to 1856. Outside of the Survey of India and its GTS project, no one seemed to know much about Sikdar’s role and feat.

The next major development related to Peak XV came on March 1, 1856 – four years after the discovery – when Surveyor-General Waugh sent an official letter to his deputy Henry Thuillier, conveying his decision to name Peak XV as ‘Mount Everest’.

That communication marked the first time that people in the Survey of India’s inner circles came to know that Peak XV was the world’s tallest mountain, and also that it was tipped to be named after Waugh’s predecessor, George Everest.

It is evident that a concerted effort was underway within the East India Company circles in Britain as well as in Dehradun to downplay Sikdar’s leading role in the findings. The confirmation of the sheepish move came five months later.

On August 6, 1856, the world came to know that Peak XV in the Himalayas was the highest mountain in the world, and that it would be named after former Surveyor-General of India, George Everest. Henry Thuillier, Waugh’s deputy at the GTS, broke the news to a gathering at the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta.

Thuillier made no mention of Sikdar and his role as the Chief Computor during that announcement.

The London Times published the news, and it was followed up by media outlets all over the world. It is not yet known if Sikdar was present in the audience when Thuillier made the announcement at the Asiatic Society. That research is underway.

The Big Deception

Clearly, the Survey of India tried to give the impression to the world that George Everest was associated with the discovery of Peak XV’s height.

Evidently, Everest had nothing to do with the effort. He had retired in 1843 – nine years before Sikdar made the discovery about Peak XV’s height – and had moved back to London after handing over the reins to Waugh in Dehradun.

Interestingly, shortly after Thuillier made the epic announcement, a few members of the Asiatic Society protested against naming Peak XV after Everest, arguing that the Survey of India should settle on a local name.

Less than three weeks after the announcement, Waugh sent a letter to Sikdar in Calcutta on August 25, 1856, writing that he hoped the Chief Computor and his team liked his decision to try to get Peak XV named after Everest.

“I am glad that the name (Mount Everest) I have given to the highest snowy peak has given satisfaction to yourself as well as other superior members of the [computor] department,” Waugh wrote to Sikdar.

In 1865 – nine years after Thuillier’s announcement – the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in London publicised the name ‘Mount Everest’. Yet again, while making the announcement, the RGS didn’t mention Sikdar’s involvement. Instead, the declaration appeared to underline the manufactured narrative that Everest himself was associated with the feat.

George Everest’s Racism

While some historical accounts say that Everest was reluctant about Peak XV being named after him, many other versions point out that he not only agreed to the name of ‘Mount Everest’, but even made an extremely racist remark about the pronunciation skills of Indians.

Multiple researchers have written that Everest mocked in the British East India Company’s inner circles, saying Indians didn’t have the capability to pronounce the word ‘Everest’ the way it should be. Apparently, the word ‘Everest’ is pronounced “eev-rest” and not “ever-est”.

Shedding light on the politics surrounding the naming of Peak XV, author Ashish Lahiri said, “Andrew Waugh was a cunning diplomat. He wanted to show that George Everest was his guru, and therefore, he suggested naming the peak after him as his gurudakshina.”

In fact, a French-style name, ‘Mont Everest’, was also suggested around the same time.

For all the talk of Everest’s initial reluctance about the proposal to name the peak after him, he eventually gave the move a thumbs-up when asked about it. After all, he knew that if the peak was indeed named after him, he would remain immortal.

‘Sheer Lies’

There was yet another controversy surrounding the naming of Peak XV. Whenever a new peak in the Himalayas was spotted by the British occupiers, a local name used to get assigned. It was an unwritten convention in the Survey of India circles.

But when it came to Peak XV – identified as the highest peak in 1852 – Survey of India officials claimed that there was no clarity on a local name, and hence, a new name needed to be brainstormed.

Author Sukumar Chakraborty slammed this narrative. “The British were playing politics with the peak’s name. They claimed they didn’t know if it had a local name. They were telling lies – sheer lies,” he said. “The Royal Geographical Society in London had prior knowledge of a map that was published in Paris long back [in 1733]. Yet, they say they didn’t know about any local name. The local name, pronounced ‘Chomolungma’, was clearly mentioned on that map. I get really angry whenever I am reminded about their lies.”

Researchers we spoke with find it shameful that Sikdar was systematically sidelined after his monumental achievement. In 1851, a year before Sikdar’s discovery, British survey authorities published the first edition of the Manual of Surveying for India. Sikdar was prominently credited in its preface as the distinguished head of the GTS’s computor department.

Then in 1859, thesecond edition of the Survey Manual was published, in which the original preface was kept intact, hailing Chief Computor Sikdar’s contribution to science.

However, the British East India Company’s attitude towards Sikdar turned cold years down the line, as evident from the following chain of events.

In 1861, Andrew Waugh retired after 18 years as Surveyor-General of India. He was replaced by Henry Thuillier. Later that year, Sikdar shot off an unhappy letter to the GTS’s head office in Dehradun, saying he wanted to resign from the Survey of India.

He argued in his letter that he couldn’t “physically and mentally” continue working. It is worth noting that he was serving in two roles at the same time – that of the GTS Chief Computor, and also the head of the Calcutta Observatory.

After receiving his letter, his superiors at the GTS advised him not to quit.

The Resignation

Sikdar’s resignation note itself was quite intriguing. Despite being a stout and fit man, with no track record of chronic health-related issues, he wrote that he wanted to quit because “physically and mentally” he was unable to do his job. In response to the letter, GTS chief James Walker wrote back to Sikdar, saying he was the “brightest jewel” on the Survey of India team, and that he couldn’t believe he wanted to quit.

Eventually, without getting any official or public recognition for his achievement related to Peak XV, Sikdar retired from the Survey of India on March 15, 1862 at the age of 49, settling into a new life in the French colony of Chandannagar.

Just as Sikdar retired, the office of the GTS Chief Computor was moved back from Calcutta to Dehradun under the supervision of new GTS head Walker. Later that year, he joined the General Assembly’s Institution in Calcutta as a senior mathematics teacher. The institution is now known as Scottish Church College.

Death Vs. Disappearance

Eight years after his retirement, on May 17, 1870, Sikdar was reported dead in or around his house in the Gondalpara area of Chandannagar town, where he spent his last years. He was 56 years old, and died as a bachelor. Nothing is known about how he died. There is no record of what happened to his body. Neither the British occupiers nor prominent Indian personalities at that time took up the matter of his mysterious death.

By the time of his reported death, the British monarchy was firmly in charge of the colonised subcontinent, having elbowed out the British East India Company in 1857. However, the British Raj, too, was hardly interested in acknowledging Sikdar’s contribution towards calculating the height of Peak XV.

In 1871, the GTS mission, essentially an intelligence project to map the subcontinent, was completed under James Walker. Four years later, in 1875, the third edition of the Survey Manual of India was published. Strangely, Sikdar’s name did not feature in it at all. The preface featuring him, which was published in the first and second editions, was dropped from the third edition.

The Friend of India, a prominent publication at that time, labelled the removal of Sikdar’s name from the Survey Manual a “robbery of the dead”. Also, British surveyor John McDonald condemned the move. However, as historians pointed out, none of the prominent Indian personalities raised their voice. Stalwarts such as Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee were around at that time, but no one said anything openly.

Nature Magazine

The first time the world came to know about Sikdar’s feat – but not his name – was on November 10, 1904, in an article in Nature magazine that was written by British army officer Sidney Burrard, who later became the Surveyor-General of India.

In the article, Burrard wrote that the Chief Computor in Calcutta was the first person to discover that Peak XV was the highest mountain in the world. He also wrote that the GTS Chief Computor – without naming him in the article – conveyed his findings to his boss Andrew Waugh.

After the partial recognition in the 1904 Nature article, 1921 turned out to be a watershed year. That’s when Sikdar’s name appeared in public domain for the first time – 51 years after his mysterious death.

British special operations expert Francis Younghusband revealed in the foreword to CK Howard-Bury’s book – Mount Everest: The Reconnaissance, 1921 – that‘Radhanath Sikdar’ was the name of the individual who discovered that Peak XV was the world’s highest mountain.

Genuine Or Fabricated Interaction?

Interestingly, Younghusband wrote in vivid detail that Sikdar broke the news about his big discovery to Waugh in a dramatic in-person interaction by bursting into his office room.

However, records show that it was impossible for Sikdar to have physically met Waugh and have that interaction, since he was based in Calcutta while his boss was in Dehradun. An exchange of correspondence was the only way he could have intimated Waugh about his findings.

Kolkata-based author Dr. Sankar Kumar Nath, who wrote a book on the mathematician titled Radhanath Sikdar: Toththyer Aloye (In the Light of Facts), trashed Younghusband’s claim. “It was a ridiculous claim. Of course, Radhanath had correctly calculated the height of the peak, and he would have communicated his findings to Waugh. But he simply couldn’t have done it the way Younghusband narrated it.

“Radhanath was working from his Park Street office in Calcutta at that time, while Waugh was based up north in Dehradun. That fact is more or less established. Therefore, it wasn’t possible for the dramatic face-to-face interaction to have happened. Sadly, Younghusband’s version of the story muddied the waters further,” said Dr. Nath.

Author Sukumar Chakraborty also doubts the claim that Sikdar broke the news to Waugh in a dramatic fashion. “It’s unlikely the incident narrated by Younghusband ever happened. Radhanath was not known to be a highly emotional person at work. From what we know of his character, he wouldn’t do something like that – rushing into his boss’s office in a dramatic fashion,” he said.

India, US, Dalai Lama

Sukumar Chakraborty said Younghusband’s revelation in 1921 sent waves far and wide. “Suddenly, the world woke up to this new piece of information about a man called Radhanath Sikdar. It sparked a buzz among Bengalis, in particular,” he said. “Younghusband’s revelation came at a time when the Dalai Lama was refusing to give the British permit to enter Tibet for survey work. An intense political tussle was underway at that time, involving the US, the Indian viceroy, and the Dalai Lama.”

“The bottom line is that people got to know from that revelation from Younghusband that Radhanath Sikdar was the man who had measured the height of Peak XV,” he said. “The truth was finally out. But then, as people started researching about Radhanath, they found that he had left nothing behind, except for a personal diary. And that diary, too, had gone missing long back.”

A few years after Younghusband’s declaration, British surveyor Kenneth Mason, who later became the University of Oxford’s first geography professor, narrated the same story in 1928.

In a speech titled ‘Himalayan Romances’ that was delivered in Shimla (now capital city of Himachal Pradesh), Mason claimed that “it was during the computations of the northeastern observations that a babu rushed on one morning in 1852 into the room of Sir Andrew Waugh and exclaimed, ‘Sir, I have discovered the highest mountain on the Earth’.”

In 1933, Sikdar’s name was once again back in the public domain, thanks to researcher-writer Jogesh Chandra Bagal, who wrote about the mathematician’s Himalayan feat, in the monthly magazine, The Modern Review.

This unverified Sikdar-Waugh face-to-face interaction has been reproduced countless times. It leaves us with an unanswered question: Why did Francis Younghusband go out of the way to credit Sikdar and narrate an incident that may never have happened?

Hidden Agenda Of The Colonisers

Was Sikdar’s feat being deservingly brought to the limelight merely as a political ploy in a tussle between rival factions of the British colonisers – the East India Company and the monarchy? Was his name being used as a pawn? Well, one can only speculate.

We know for sure that during the time Sikdar completed his Peak XV mission, the change of colonial control was looming. After the Rebellion of 1857, the monarchy took charge of India, and the East India Company – Sikdar’s original employer – was sidelined.

So, the question is, was Sikdar’s feat being brought back from the cold storage by India’s new colonisers (monarchy) in order to expose that the old colonisers (East India Company) had tried to suppress his achievement?

The radio silence in Britain about Sikdar was broken yet again much more recently, in 2000, when British historian John Keay wrote in one of his works that “Sickdhar’s computations provided the first clear proof of Peak XV’s superiority”.

The Refraction Factor

Sikdar was entrusted with the big mission especially after having left Everest impressed for deftly operating the ‘blue lights’ and mastering the ‘ray trace method’ during survey work in the Jumna region of the Delhi zone, writes Ashish Lahiri in his book, Radhanath Sikdar and Colonial Science: An Indian Surveys an Uncharted Terrain.

When the Himalayan mapping mission was underway, the readings of Peak XV and the surrounding mountains sent in by the surveyors initially appeared muddled, erroneous, and extremely confusing.

That is when the mathematical genius of Sikdar came into the picture.

Waugh entrusted his Chief Computor with the task of making sense of the chaos. Sikdar started brainstorming, and discovered that the ‘refraction’ – the bending of light due to varying densities of the atmosphere – needed to be understood and factored in to be able to correctly calculate the height of the peak.

“Today, we speak very easily of atmospheric refraction. But the phenomenon wasn’t well known during those days,” said Ashish Lahiri. “Radhanath made a breakthrough after analysing the raw data from the readings. He established that refraction had influenced the readings of the peaks, and that it needed to be taken into account to get the conclusion right.”

In addition to weeding out refraction from the tricky readings, Sikdar also had to consider the seasons in which the readings were taken and the respective atmospheric temperatures, according to Dr. Sankar Kumar Nath.

“Seasons and temperatures were important factors because in colder weather, there is extra snow on the peaks as compared to warmer times,” Dr. Nath explained. “So, refraction apart, Radhanath also had to take into account the time of the year when the readings were taken in order to eliminate the element of extra snow on the peaks. Basically, it was an extremely difficult job.”

Method Of Minimum Squares

Working from his Calcutta office, Sikdar came up with an advanced version of the ‘Method of Minimum Squares’ or ‘Least Squares’, which was originally conceptualised by English mathematician Roger Cotes in 1722. The method helps scientists eliminate errors by listing out the percentages of errors from various readings, factoring them in, and minimising them.

Encouraged by Waugh, Sikdar was able to accomplish his feat because of his bold decision to apply his own version of this method to weed out errors from the Peak XV readings. Essentially, he mastered European mathematics and applied it well.

In fact, writer Ashish Lahiri says with conviction that Sikdar was a professional scientist, but wasn’t recognised as one during his time. He provides multiple arguments to back the claim.

“Look, Radhanath had acquired solid theoretical training in mathematics and physics. His job involved dealing with large-scale scientific observations made with the help of sophisticated instruments. He earned his living by practising science. He made original contributions in his field. Plus, he drew recognition from his peers – aren’t all these arguments enough to conclude that he was a scientist?” argued Lahiri.

Sikdar, The Rebel

It might seem that Sikdar would have been a loyal employee of the British East India Company for having been entrusted with the prestigious Peak XV project. In reality, it was quite the opposite.

There are multiple examples of the mathematician repeatedly taking on the British colonisers. The most famous one among them was a lawsuit that he faced in 1843 for protesting over the racist mistreatment of Indian labourers by a high-ranking British official.

Citing historian Sivanath Shastri’s works, Ashish Lahiri narrates the story in vivid detail in his book, Radhanath Sikdar and Colonial Science: An Indian Surveys an Uncharted Terrain. The gripping story of the legal case was published in three issues of The Bengal Spectator, on May 17, September 1, and September 16, 1843.

An Epic Fight

The story unfolds like this. On May 5, 1843, when Sikdar was posted at Dehradun as a member of the GTS computor department, District Magistrate Henry Vansittart ordered Sikdar’s workmen to work for him as his coolies, and he went on to physically mistreat them.

When Sikdar got to know about the dark episode, he immediately protested over the District Magistrate’s acts, calling them a labour rights violation. In a dramatic turn of events, he stepped in and disallowed his workmen to work as Vansittart’s coolies.

Enraged over Sikdar’s unprecedented show of defiance, the DM prosecuted him, dragging him to court. Sikdar didn’t get any support from his bosses in the Survey of India, and fought his case entirely on his own for months. After doggedly standing by his decision to challenge Vansittart, Sikdar was fined Rs 200 by the court.

It is quite possible that the Sikdar-Vansittart spat may have spurred the Survey of India to eventually move the GTS Chief Computor out of Dehradun in 1849, and post him in faraway Calcutta until his retirement. Otherwise, the man heading the high-stakes Himalayan mapping project should ideally have been operating from the GTS’s Dehradun HQ.

Anger Over Wages

On another occasion, he vehemently protested over the below-par working conditions and low wages for the East India Company employees at the Calcutta Observatory, when he was posted there as the met office head. On May 23, 1853, he shot off a stern letter to his GTS higher-up, Henry Thuillier, seeking justice for the Calcutta-based computors and observers.

Sikdar, who was a Derozian, also emerged as a leading campaigner of women’s rights, especially widow remarriage, when he was posted in Calcutta. In 1854, he brought out a revolutionary women-focused publication called Mashik Potrika (‘monthly magazine’) along with his friend Peary Chand Mitra, also known as Tekchand Thakur.

In the one-of-its-kind outlet, Sikdar experimented with a lucid writing style with the aim of making household women, and not just the intellectual class, take an interest in Mashik’s writings. Introducing an easy-going writing style in published form during those days was considered a novel and bold act.

Heated Exchanges

The British got a further taste of Sikdar’s defiant nature when the Chief Computor in Calcutta often exchanged heated official correspondence with his boss Waugh in Dehradun. But his rebellious nature didn’t seem to come in the way of the task assigned to him as he went on to correctly discover the height of Peak XV.

Then there is a story from 1838 when Sikdar was drawing a monthly salary of Rs 173, but was unhappy at getting underpaid compared to his British colleagues. In protest, he took up a job offer to teach at a public institute. But the move was disallowed by the GTS. Soon after, the Survey of India banned its Indian employees from quitting and taking up other jobs without consent.

Many years later, a defiant Sikdar yet again ruffled a few feathers when he applied for the job of a magistrate in Calcutta in 1850 despite knowing the Survey of India’s rules. Expectedly, his immediate superior, Waugh, refused to let him go.

In another act of social defiance, some records claim that Sikdar was immensely fond of eating beef, and even advocated it. In April 1881, 11 years after his presumed death, Calcutta Review reported that he once wrote in his personal musings, “India would never become a great nation till its inhabitants made use of a diet consisting extensively of beef.”

Research Hub In Chandannagar

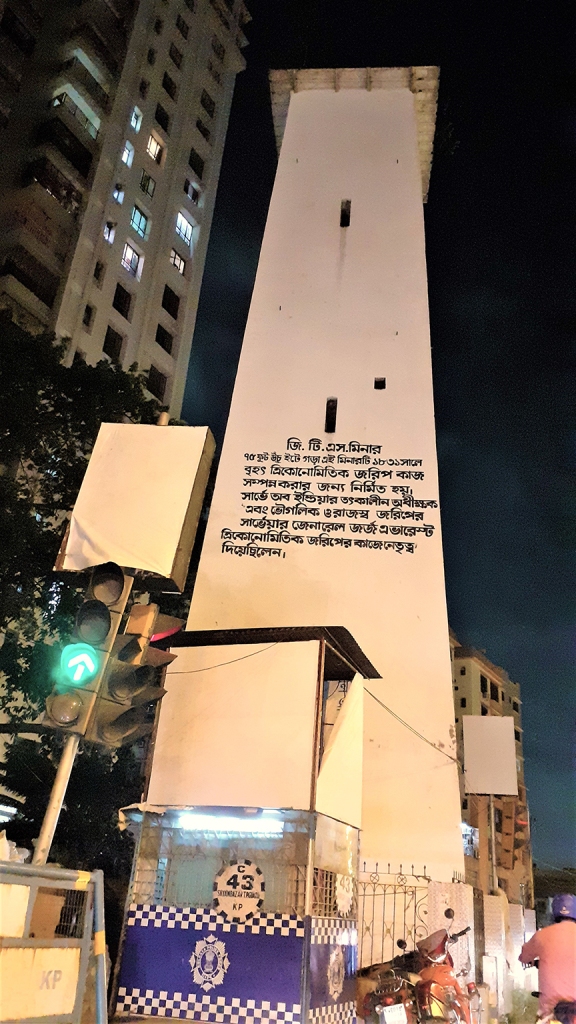

In the breezy town of Chandannagar – originally known as ‘Chander Nogor’ – in Bengal’s Hooghly district, a short walk from the riverside Strand Road and into the Bagbazar area will take you to a research centre called ‘Giri Doot’. It hosts the Radhanath Sikdar Himalayan Museum and the Rashbehari Research Institute.

The research hub is headed by Kalyan Chakraborty, who is an educator, philanthropist, mountaineer, globetrotter, and artefact collector. He runs it along with Lipika Ghosh, a mountaineering veteran.

The place stands out as the only information base dedicated exclusively to Sikdar. Giri Doot is an idea exchange hub where local and foreign students drop by to research on the lives of Sikdar and former Indian revolutionary hero Rash Behari Bose, under Kalyan Chakraborty’s guidance.

The sprawling, atmospheric building from the old days has an entire wing dedicated to Sikdar – like a quaint pilgrimage site – with a bust displayed along with a vast collection of vintage newspaper and magazine coverage of Sikdar as well as various mountaineering feats.

The Sikdar enthusiast laments that while most Indians aren’t aware of his feat, those who somewhat know about Sikdar don’t know much outside of his connection with Peak XV.

“The sad part is that those who know a little bit about Radhanath Sikdar don’t know that he was a huge figure outside of the Everest story,” said Kalyan Chakraborty, who laments that Sikdar hasn’t received proper recognition at the government level. “Radhanath was much more than what people think he was. He was the Indian subcontinent’s first documented freedom fighter. Do many people know that? I don’t think so,” he said.

“That apart, he was one of the first scientists of India. Also, he used to fight with the British for the rights of labourers. He was deeply involved in running Mashik Potrika, a revolutionary monthly magazine on women. So, Radhanath Sikdar had much more to do than just Mount Everest.”

The Cemetery Mystery

One of the many mysteries and incredible stories surrounding Sikdar’s life is a certain claim that has been floating around since 2011, further muddying the waters about his hazy last years.

For about 12 years now, many people have been under the impression that Sikdar had converted to Christianity from Hinduism, and that his grave has been located at a cemetery in Chandannagar.

Those who believe in this story say with conviction, but without any direct evidence, that Sikdar’s mortal remains lie under a certain concrete grave in the middle of the Sacred Heart Cemetery, next to St. Thomas Primary School.

Empire Diaries visited the disputed grave, and learnt from multiple eyewitness accounts who visited the site before and after the so-called ‘discovery’ that the tomb had been lying there unmarked for years, possibly decades. But once the claim about Sikdar was made, enthusiasts teamed up with the cemetery’s caretakers and a section of the nearby French colonial-era Sacred Heart Church. Together, they decorated the newly ‘discovered’ grave and placed Sikdar’s name on it.

Author Ashish Lahiri, who invested his lifetime probing Sikdar’s life, visited the church to verify the claim. “I gave them a visit and had a good look at the papers the church has about those who are buried at the cemetery,” said Lahiri. “I did not find Radhanath’s name on those lists. In the papers that I accessed for burials there on the stated date of his death [on May 17, 1870] and on dates around it, his name is not there.”

It is understood that all burials at that cemetery are supposed to be recorded, with the Sacred Heart Church keeping day-to-day records of the names of the deceased buried there. In fact, this system of churches keeping records of burials at cemeteries under their jurisdiction is a convention followed all across Christianity for centuries.

Sceptics have been asking that if we are unable to find Sikdar’s name in the church’s record books, then it is highly unlikely that his mortal remains lie inside that cemetery.

Lahiri is puzzled over the whole episode. “I saw the grave. The look of it didn’t seem logical to me. He was a famous man, after all. I spoke with the father at the church after failing to find Radhanath’s name in the burial records. He pointed out that we shouldn’t assume that all the papers are systematically in order. It could be true. After all, the church has been around since the 18th century,” said Lahiri.

Sikdar’s obituaries didn’t mention any graveyard, and they also didn’t raise any questions about the lack of basic information surrounding his death. “It is as if Radhanath has been wiped out of history,” said Lahiri.

Tushar Bhattacharya, a Chandannagar-based former government-level survey officer who spent his lifetime researching about Sikdar, is sceptical that the grave is genuine. “I have known this story right from the start. I don’t think I would conclude that the grave in question belongs to Radhanath. So far, I have not found any evidence that confirms it,” he said.

Writer Sukumar Chakraborty, who wrote a book on Sikdar, added another interesting angle to the puzzle. He recounted that the church authorities had politely turned him away when he wanted to see the burial records at the time of researching for his Bangla book, Radhanath Sikdar: Itihaash-er Tragic Nayok. “Maybe we can explore the idea of looking for the record in the archives of St. Xavier’s College in Kolkata,” he said.

Did Radhanath Sikdar Convert?

While the sensational claim about the grave was made only recently, speculation about whether Sikdar had become a Christian has been raging for many years.

There is no concrete proof or documentation showing that he had converted from Hinduism to Christianity, but there are a few compelling instances of circumstantial evidence that point towards that possibility.

Kolkata-based Sikdar enthusiast, Dr. Sankar Kumar Nath, made a significant breakthrough in his 2012 book, Radhanath Sikdar: Toththyer Aloye. According to his research, which he said he “accidently bumped into while rummaging through heaps of documents”, English journalist and historian John Clark Marshman claimed that Sikdar had been baptised.

According to this narrative, Marshman, while testifying before the Select Committee on Indian Territories on July 21, 1853, made a claim that Sikdar had converted to Christianity “towards the end” of 1852. “I will particularly mention the case of an individual of the name of Radhanath Sikdar… He threw up his own creed, and embraced Christianity, and has been baptised,” Marshman told the Select Committee, according to Dr. Nath’s research.

Another thought-provoking piece of circumstantial evidence supporting the Christianity hypothesis is a so-called first-person account of Sikdar that has been republished across multiple publications.

According to this narrative, Radhanath apparently wrote about his father Tituram’s thoughts in his diary sometime in 1853. The mathematician reportedly wrote that his father “regretted three things” towards the end of his life – “going blind, his daughter not having any children, and Radhanath not staying a Hindu”.

Then there is yet another narrative, which says that since Sikdar was well-accepted by high-ranking British officials such as George Everest and Andrew Waugh and occasionally got to dine with them, chances are that he may have won over their confidence by becoming a Christian.

According to this argument, the classist British officials wouldn’t have given Sikdar this rare social access (read: privilege to have meals together) had he not leaned towards the colonisers’ religion.

Nothing Conclusive

While all these claims could be true, they can also be written off from a critical-thinker’s perspective.

One, how do we know whether Marshman was speaking the truth before the Select Committee? It is quite possible that he may have fabricated the story to brag about the success and penetration of Christianity in the British colony. It is only his claim, after all. We don’t know if Marshman produced evidence while making the claim before the committee.

Two, the reported narrative about Radhanath writing about his father Tituram’s thoughts in his personal diary can only be verified once the diary itself is located. The diary has been missing for a long time, and researchers are desperately looking for it.

Three, while there are multiple references saying Sikdar sometimes broke bread with his British superiors at work, neither do we have concrete evidence of it, nor can that be a basis for concluding with certainty that he had become a Christian.

So, the jury is still out.

An Amusing Story

Dr. Nath recalled an amusing turn of events when he travelled to Chandannagar from Kolkata to try and find out if Sikdar was buried there – now that he was armed with circumstantial evidence of his conversion to Christianity.

“I made two visits to that cemetery – once before the buzz about the grave began, and a second time after the grave became a talking point,” said Dr. Nath.

“On my first visit, I looked around for his grave. There was nothing. When I asked around if anybody had any idea, I was told there was no such thing there. But during my second visit to the cemetery, I found that a grave, which was earlier lying there unmarked, had been decorated and marked as Radhanath Sikdar’s grave,” the doctor said.

“When I asked the people at the cemetery how they got to know about Radhanath Sikdar’s grave, I was told they started actively looking for it after an author in Kolkata wrote a book revealing that Radhanath had become a Christian,” said Dr. Nath, adding, “I realised they were referring to the book that I had written! So, on the basis of what I wrote, they suddenly seemed to have located Radhanath’s grave in Chandannagar! It was an amusing moment.”

While there is no confirmation if it is indeed Sikdar’s grave, his Wikipedia page claims he was buried at the Sacred Heart Cemetery in Chandannagar. Expectedly, the information website doesn’t corroborate it with evidence.

Meet Sandip Sikdar, A Descendant

Sandip Sikdar is a bustling journalist in his mid 30s, who writes on sports events for Delhi-based English newspaper Hindustan Times. A genial man who is well-known in the Indian capital’s sports journalism circles, Sikdar hardly ever told his colleagues and mates in the newsroom that he is a descendant of the man who calculated the height of Peak XV.

Sandip is a descendent of Srinath Sikdar, who was Radhanath’s brother. Yet, despite the Sikdar family’s blood running in his veins, Sandip says many members of his extended family don’t know much about Radhanath beyond the Peak XV story.

“Most of my relatives, whether they are of my generation, or that of my father’s, are always ready to claim allegiance to Radhanath, though most know very little about him. Even those folks who married into other families and don’t have ‘Sikdar’ as a surname are ready to claim allegiance,” Sandip told Empire Diaries.

“It is probably a very human thing to relate to someone or something famous. They know what he did and that we are related, but they know little more than that. Rather, they rely more on television media when they run debates about renaming the mountain after Radhanath,” Sandip said.

Sandip was keen to know more about Radhanath from his childhood days, and did a dissertation on his ancestor while he was in college. “As things start getting older, real stories become legends and it becomes nearly impossible to separate fact from fiction. I myself learnt more about Radhanath from research than from my family.

“I gained interest when the Indian government issued a stamp in Radhanath’s honour [on June 27, 2004]. I did a college project on him a few years later, again, basing my knowledge more on books, libraries, and the internet, rather than oral history,” he said.

Sandip laments that his extended family doesn’t have a comprehensive grasp of Radhanath’s life story because of a lack of sufficient data, even though there is a good amount of trusted research to go by.

“There is no concrete data available,” Sandip said. “I am sure most of them (members of my extended family) won’t even know what the Survey of India or the Great Trigonometric Survey was. I realised there is a lack of concrete data when I was researching in college.

“Back in those days, we were very poor at maintaining data and records in comparison to the British who ruled us. And another reason why the family or rather today’s generation knows so little about Radhanath Sikdar is because their interest ends at his greatness.”

Truth Vs. Oral History

Sandip has heard from his family elders that Radhanath was treated as a social outcast. “It was perhaps because he stayed, lived, and behaved more like Britons than an Indian, which challenged the norms of 19th-century society. But then again, it is all hearsay. That is the thing with oral history. It sounds fascinating, but you will never know the truth since it gets mixed with fiction as information is passed down generations,” he said.

Do Sandip’s family members know that Radhanath was a documented protester against British mistreatment of Indian labourers; that he edited the subcontinent’s first ever women’s journal, called Mashik Potrika; that he revolutionised mathematical models such as the Method of Minimum Squares; that he revolutionised meteorological measurements systems as the Calcutta Observatory’s head; and that his pathbreaking meteorological log book is sometimes used at Kolkata’s met office even today?

“Even I didn’t know some of this, let alone my family,” Sandip candidly said. “But I assume my grandfather’s generation perhaps was more aware of all this. Today, most Indians, including his descendants, are only bothered about the greatness of his accomplishment [related to measuring Peak XV’s height]. What he did after that doesn’t matter to them.”

Some of the things about Radhanath that Sandip has heard from his family elders are that “he was a great man”. “But everything stops at calculating the height of Everest. I have also heard that he earned pretty well, used instruments completely unknown to his family, and had contact with very few members of his family,” the sports journalist said.

When Sandip first heard about the hype surrounding a grave in Chandannagar, he felt the claim that it could be that of Radhanath was not worth pursuing. “I heard about it, but I never gave it too much importance. I think we should move on. I don’t see the point in investigating it. But that doesn’t mean I am discouraging anyone who wants to research it.”

Chandannagar’s Gondalpara House

A short ride from the riverside stretch of the Strand Road in Hooghly district’s Chandannagar town will take you to the quiet and clustered middle-class neighbourhood of Gondalpara.

Right in the middle of the locality, and accessible via a network of narrow lanes, lies a small stretch of a street officially called ‘Radhanath Sikdar Road’. Residential houses line up either side of the street. One of them is a three-storied house that stands out for its garish colour combination of blue, yellow and pink.

The new-look building is owned by the Bengali-speaking Samanta family. It was built a few years back after bulldozing an earlier building that stood there once – apparently owned during the 19thcentury by its resident Radhanath Sikdar, of which there is no proof yet in terms of property-related paperwork.

Both Sukumar Chakraborty and Ashish Lahiri have photographs of the original building in Gondalpara where Sikdar is presumed to have resided.

Patch Of Concrete: Is It Concrete Evidence?

While the original building is now gone, replaced by the three-storied apartment block, the Samanta family has mindfully kept some remnants from the past intact. One of them is a patch of concrete on the floor that lies adjacent to the new building, which the residents say is a part of the floor of the demolished building.

Another remnant from the past that can still be seen at the site is, what the residents claim, the original washroom from Sikdar’s time. While a section of the standalone washroom has been renovated, the rest of it stands untampered, its bare bricks sticking out, braving decay, dereliction, moss, and weeds.

Empire Diaries caught up with the Samanta family, and learnt that they are well aware of the historical value of the place, even though the matter is disputed. Mithu Samanta, who resides there, recalled that she learnt about the importance of the address after moving in following her marriage many years ago.

“I got married in 1995. As I moved in, I learnt from my family members here that Radhanath Sikdar used to reside here many, many years ago. Radhanath’s original house had been bought over, and much later, it was taken up by the Samantas long before I arrived here,” Mithu said.

After welcoming us to have a look at the remnants of the earlier house – the concrete patch and the original wing of the washroom – Mithu said Sikdar enthusiasts keep dropping by from time to time to have a look at the place, showing the enthusiasm of pilgrims.

“So many times, we have seen aged women and men come here, caress the remnants, and take away parts of the bricks as mementoes,” Mithu recalled. “I remember one such elderly woman who came here, got emotional, cried a lot, and took permission from us to keep a brick with herself. All sorts of curious enthusiasts drop by. That’s why, we have kept the concrete patch and the washroom intact as memories for Radhanath fans to come and see.”

‘Show Me The Evidence’

A few kilometres from the intriguing location in Gondalpara, Bagbazar’s Kalyan Chakraborty isn’t convinced that it is the site of Sikdar’s house. “How can we say with conviction that Radhanath’s house stood there once upon a time? Where’s the proof? If it was indeed his residence, there must be some scrap of paper corroborating the claim. Can someone show me the evidence? I will be glad to see that,” he said.

“Since this is a riverside town, lying adjacent to Hooghly River, it is quite possible that Radhanath’s original house was perhaps washed away, you never know. The point is, without some kind of proof of ownership history of the house or the site, I don’t think we can safely conclude Radhanath lived there,” said Kalyan Chakraborty.

In a stark counterclaim, Bimalendu Bandyopadhyay writes in his book, Gondal Para: Past and Present, that “the house hallowed by Radhanath Sikdar still stands in the Gondal Para area”, referring to the old villa-style building that was demolished to build the existing apartment block.

Bandyopadhyay also writes in his 2003 book, “In order to preserve the memory of Radhanath Sikdar, Chandannagar’s municipality has changed the original name of the neighbourhood from Haldar Para to Radhanath Sikdar Street.”

But Bandyopadhyay doesn’t back his claim in the book with evidence showing Sikdar indeed resided there. So, the argument continues.

Photo Or Painting?

There is a lot of speculation surrounding the visual representation of Sikdar. The only available image of the Indian mathematician that is republished everywhere is actually an oil painting, not a photograph, as pointed out by Dr. Sankar Kumar Nath, who wrote a book titled Radhanath Sikdar: Toththyer Aloye.

Kolkata-based Dr. Nath believes Sikdar’s oil painting was made by John Peyton, another surveyor with the Survey of India at that time. “Thank goodness, Peyton made that oil painting of Radhanath. Otherwise, we may never have had a proper look and feel of the man,” Dr. Nath said. “Peyton was a well-known painter in the Survey of India circles. At that time, photography was a costly affair. Also, the technology wasn’t easily available. That is why, oil painting was the norm.”

Dr. Nath said Bourne and Shepherd, a renowned photographic studio during the 19th century, opened a branch in Calcutta in 1867. But that technology came to Sikdar’s vicinity much too late – he was reported dead just three years later, in Chandannagar.

Chandannagar-based author-historian Sukumar Chakraborty recalled that Sikdar’s so-called photo – which now emerges to be a possible painting – was first published in 1922 in the book Bonger Bahire Bangali, written by Gyanendra Mohan Das. Then in April 1933, it was published again, this time in an English publication called Modern Review.

Should Mount Everest Be Renamed?

There is a raging debate and a deep divide in personal opinions when it comes to the million-dollar question – since Peak XV was wrongfully named after George Everest, should it be renamed after Sikdar?

Some Sikdar enthusiasts firmly believe that it should be named after the Indian mathematician as ‘Mount Radhanath’ or ‘Mount Sikdar’. But many others strongly feel the need to bring back one of the local names.

There are some Sikdar supporters in Chandannagar in Kolkata who send letters to the Indian government from time to time, requesting that George Everest’s name should be scrapped, and Peak XV should be renamed after the Indian scientist. They argue that since it is well-documented that Everest himself was not at all involved in the calculation of the mountain’s height, the credit should be given to Sikdar.

“There are two factions with contrasting opinions on the debate of renaming the peak,” said Sukumar Chakraborty. “One faction says it should be officially named after Radhanath. Another faction, which includes me, feels it should be officially named ‘Sagarmatha’ or ‘Qomolungma’. My question is, why should it be named after George Everest or Radhanath Sikdar?

“Radhanath only did the calculations. So, let us not become emotional. He was a skilled and talented mathematician who did the calculations, no doubt about that. But he didn’t achieve it all by himself. A huge team was behind the effort.”

Sukumar Chakraborty added, “At the end of the day, the name ‘Mount Everest’ came from colonial pressure and politicking. To tell you the truth, the mere mention of ‘Mount Everest’ makes me sad. It really shouldn’t have been named after him. I have moved away from this name-game. I thank Radhanath for what he did. But at the same time, I have a liberal opinion on this matter.”

Writer-historian Ashish Lahiri, too, doesn’t believe that Sikdar alone should be credited. But he feels both George Everest and the Chief Computor should be jointly recognised – if at all the name ‘Mount Everest’ should be changed.

“Just like it is wrong to call it ‘Mount Everest’, it will also be wrong to name it only after Radhanath. That will give the wrong impression that Radhanath achieved the feat all by himself,” Lahiri said. “The fact is, Radhanath himself had never done any of the field survey for the project. But still, since what he did was vitally important, there can be a compromise formula. Everest’s name can be kept presuming he represented Europe’s scientist community. So, a proposed name for the peak can be ‘Mount Everest-Radhanath’ or ‘Mount Radhanath-Everest’.”

Kalyan Chakraborty, who runs the Radhanath Sikdar Himalayan Museum in Chandannagar, believes that it is necessary to constantly remind the Indian government and other authorities that Sikdar must get the recognition he deserves – whichever way that comes. “Due recognition is the whole point – that is what will eventually make coming generations know about Radhanath Sikdar,” he said.

The Silence Of George Everest

Dr. Sankar Kumar Nath usually praises George Everest for his handling of the Great Arc project, but he laments that the former Surveyor-General of India never publicly credited Sikdar for calculating the height of Peak XV.

“Ever since the mountain was named after him, George Everest has never in his lifetime spoken about Radhanath publicly. I have invested a lot of time trying to find out if he ever mentioned him somewhere in public, but I couldn’t find any resources,” said Dr. Nath.

The name-game was a murky affair right from the start, as evident from an official letter sent by Surveyor-General Andrew Waugh in Dehradun to Sikdar in Calcutta on August 25, 1856. In that piece of correspondence, Waugh appears to be giving an explanation to the Chief Computor, arguing why he wanted to get Peak XV named after George Everest instead of picking one of the local names.

“If it (Peak XV) has a local name, which is doubtful, it can only be ascertained by travelling to its neighbourhood in Nepal, which is a political impossibility,” wrote Waugh to Sikdar – 19 days after the Survey of India’s Henry Thuillier broke the news that Peak XV was the world’s tallest mountain. “There was, therefore, no alternative but to assign an appropriate name to the mountain…”

It is an irony that both Radhanath Sikdar and George Everest had never seen Peak XV in person. That is because they never went on surveying missions for that project.

Author Ashish Lahiri has a copy of this tell-tale letter, which he found at the National Archives of India in New Delhi during an investigative trip to the capital city. He published the full text of the letter in his book, Radhanath Sikdar and Colonial Science: An Indian Surveys an Uncharted Terrain.

Was Radhanath Sikdar Silenced?

In the mesh of mysteries that cocoons Sikdar’s life, the most outstanding puzzle is his hazy death – rather, his disappearance. Perhaps, his demise wouldn’t have remained as a big mystery had it been a natural death, one might speculate.