Leaving India, Finding Bharat (Part 2)

Ratna and Nadim Siraj

EmpireDiaries.com

EMPIRE DIARIES ON ROAD

April 22, 2024: From January to April in 2024, Empire Diaries founding editors, Ratna and Nadim Siraj, were on a lengthy road trip, spanning 13 states and covering nearly 7,500km. Delhi NCR was the start and finish for the journey.

The route map roughly resembled a triangle. They started off in the north, then headed east. After a pause in Bengal, they headed west across central India, reaching Goa, before meandering back to the north. They journeyed through UP, Bihar, Jharkhand, Bengal, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra, MP, Rajasthan, and Haryana.

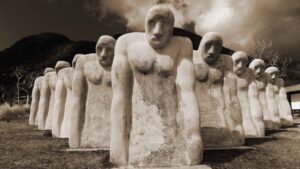

What was the motive of the road trip? To discover ‘Bharat’ that is buried underneath the more celebrated ‘India’. To make sense of the rural-urban divide. To collect compelling ground reports from the country’s rural heartland. And to piece together photographs of the hinterland.

Here goes Part 2 of a photo feature series from the discover-Bharat tour (Click here for Part 1). Part 2 also focuses on the people we met during the journey. This second part features images from Odisha and Chhattisgarh. Keep an eye on Empire Diaries for Part 3, to be published soon.

Part 2 (Odisha and Chhattisgarh)

Click here for Part 1. Coming Soon: Part 3.

COPYRIGHT & REPUBLISHING TERMS:

All rights to this content are reserved with Empire Diaries. If you want to republish this content in any form, in part or in full, please contact us at writetoempirediaries@gmail.com.

ALSO SEE…

ALSO SEE…